Giza Ground Truth: Magnetic Anomaly Surveying

By Glen Dash

At Giza we face such an enormous task in trying to determine the

footprint of the Old Kingdom complex that Glen Dash, one of our supporters

and an expert in remote sensing, suggested magnetic anomaly surveying as

another method for locating structures. Glen joined us this past winter

to test the technique. – Mark Lehner

The sand movers had finally done their job. I was now standing

on clean sand, on a layer which just days before was two meters below the

surface. The Giza Plateau Mapping Project was moving outward from

its home base in what we call Zone C. My assigned task was to magnetically

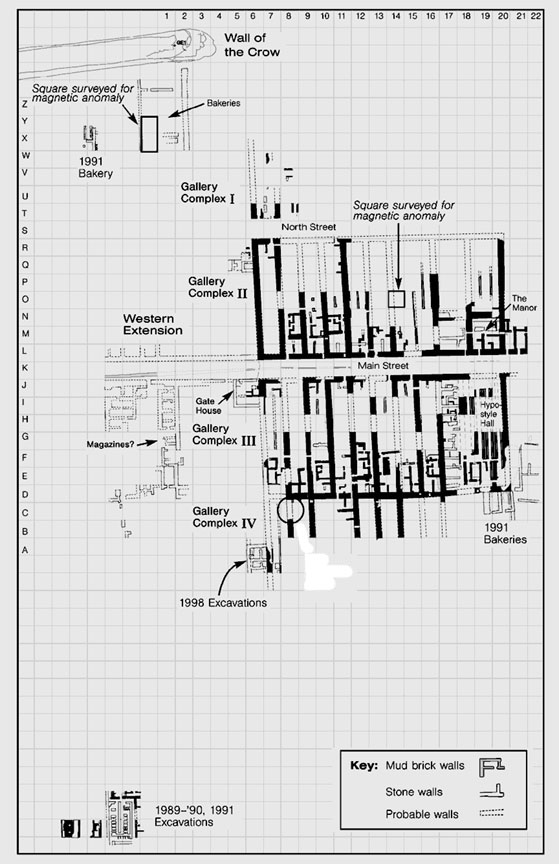

map an area which was off of our charts. Our survey map (see Figure 1) extended as far north and west as square

R4. This day I'd be working in a square without a name. We had

run out of numbers.

I had near perfect conditions for using magnetic gradiometry which measures

small perturbations in the earth's magnetic field. Iron is one of

the most plentiful substances in the earth's crust, and most every bit of

iron, to one degree or another, perturbs the earth's magnetic field.

Some materials, such as limestone and sand, produce little perturbation.

Others, like fired pottery, produce surprisingly strong magnetic fields

and, if massive enough, can be detected a meter away.

Modern Debris Wreaks Havoc

Magnetic survey is not easy. It's made difficult, in part, by

the effects of modern man on his environment. We drop little bits of

metal everywhere. On the surface of the Giza Plateau there are horseshoes,

rusted pots and pans, bottle caps, and even truck parts. We dug up

all of those things during our spring 2000 season. Bits of manmade forged

or cast iron serve to concentrate the earth's magnetic field intensely.

In fact, they will mask any archaeological features for a distance of a

meter or more. Scatter enough horseshoes, nails, bottle caps, and pots

and pans around a site and you'll see nothing of the ancient architecture.

Initially, I had signed on to work in Zone W (for west) and had attempted

to map magnetic anomalies without removing the top few feet of sand which

contains all this modern debris. In one 20 x 20-meter square I located

and removed ten pounds of junk metal, including 20 horseshoes. In

an adjacent square, slightly lower in elevation than the first, it was pots

and pans. Still farther to the north and west, a 20 x 20-meter square

revealed hundreds of bottle caps. I could discern the modern occupation

patterns from the junk I was finding.

A Fresh Start

This new area that I was assigned, however, was just cleared by the

bulldozers. They had pulled away a good two to three meters of the

sandy overburden and, at the same time, removed all the modern metal (including

what looked like the front end of a tractor). The surface I was standing

on now had been deposited here some time between 500 and 2500 BCE.

We know that because it was below the level of nearby Late Period burials

(circa 500 BCE), but above the Old Kingdom architecture. Lighter in

color than the sand on the surface, it was pristine and uniform, indeed,

quite beautiful. The Old Kingdom architecture was still probably one

or two meters beneath my feet. Nothing on the surface gave a clue as

to what might lie below.

Surveying

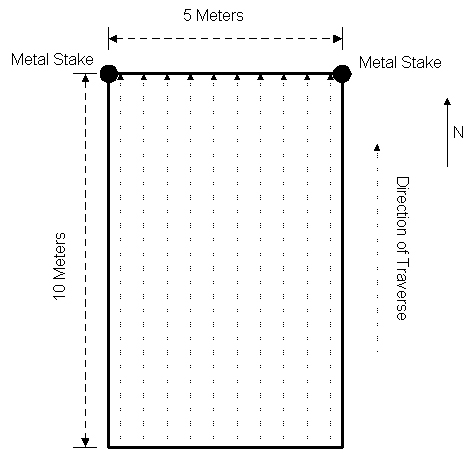

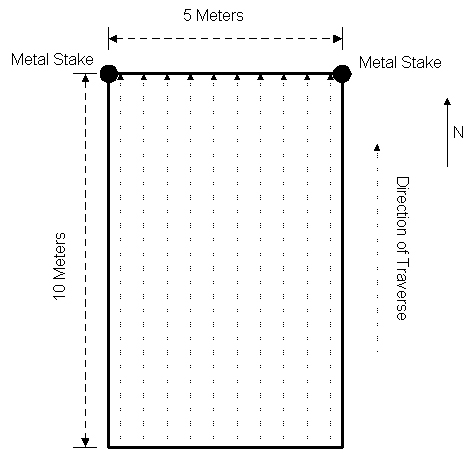

To start, we laid out a square 5 x 10 meters (Figure

3). Our ever efficient surveyor, David Goodman, had already put

metal rebar on one end of the square, but I had managed to get there before

he had done the same to the other. I placed plastic pegs at that end

of the square and laid out tapes, forming two tracks, one meter apart.

Each fiber glass tape was marked with a distinctive red marking every meter.

Once tapes were in place, mapping went speedily.

The instrument I was using, the FM36, was built by Geoscan Research.

Unlike other magnetometers and magnetic gradiometers, this one had been

designed specifically with archaeology in mind. Even though the design

was old (circa 1985), it was still the best instrument for the job.

Taking Readings

I began by standing near the southwest portion of the grid square.

Flipping the magnetometer on, it started taking readings -- four a second.

The job of the surveyor is to walk steadily and to make sure that the gradiometer

is aligned with the red markings on the tape each time the instrument beeps,

denoting another one-second interval. (See Figure 2.)

As I reached the end of the square, the gradiometer stopped beeping

(it knows that this is 5 x 10 meter square). Then I walked back to

the southern end of the square and repeated the process, this time walking

between the two tapes, which were placed one meter apart. I repeated

this process again and again, periodically stopping to move the tapes along

the 5-meter breadth of the square.

Suspense: Downloading

It is not really possible to get an indication of what the instrument

is finding by watching its readings as one walks along. There is

just too much information. So there is a moment of suspense when it

is time to download a day’s worth of data into a computer so it can be observed.

The suspense is heightened by the fact that the 15-year-old serial communication

technology used in the FM36 is incompatible with the serial input port of

newer computers. A practical alternative is to use an old computer

for downloading data. I used an old Toshiba Satellite laptop based

on Intel 286 technology.

I brought the FM36 back to the storage tent. It provided shade

and a table for the computer and the FM36. The FM36's shipping case

served as a chair. Hooking the serial output port of the instrument

to the serial input port of the laptop and firing up, Geoscan Research's

"Geoplot" software got me to the download screen. Setting the input

parameters, I pressed download and prayed that, today, the two machines

would talk to each other.

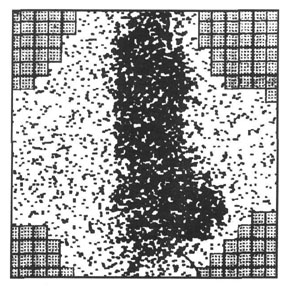

They did. I pressed a few more buttons and a 5 x 10-meter scale map

appeared on the screen. What appeared was without a doubt evidence

of an Old Kingdom structure (Figure 4). This established

that the AERA site extended far beyond the area that we had been excavating,

right up to the base of the Wall of the Crow.

Moment of Truth

Reis Ahmed's crew was now assigned the task of removing the clean sand

above the feature I had detected. I climbed atop of the Wall of the

Crow, 10 meters to the north, to watch. One foot of sand was removed,

then two, then three, revealing nothing. But something had

to be there. I stayed despite the increasingly skeptical look on the

Reis Ahmed’s face.

Almost a meter and a half down, the edges of a structure emerged. With

a bit more excavation, we could identify it. It appeared to be either

a bakery or the area immediately adjacent to one. The strong magnetic

signatures were caused by dozens of bread moulds used and discarded here.

They had piled up against the walls of a building, along with other pottery.

Using Magnetometry

My visit to the pyramids was as much to study magnetometry as it was

to study archaeology. Every site has unique characteristics, and it sometimes

can take considerable time and effort to determine what conditions will

produce useful results. Here at the Giza Pyramids magnetometry can be a

powerful and very revealing technique. The key is to strip off the modern

layers, layers which are contaminated with modern metal. Once you reach

a depth that precedes the Iron Age, there should be no refined iron to cause

interference. (It would also help if archaeologists found some other

way to stake the corners of their squares than to use iron rebar.)

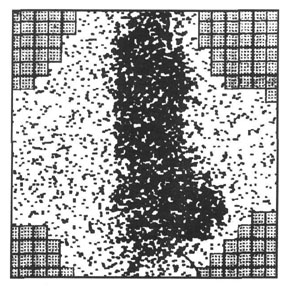

Finding Ghosts

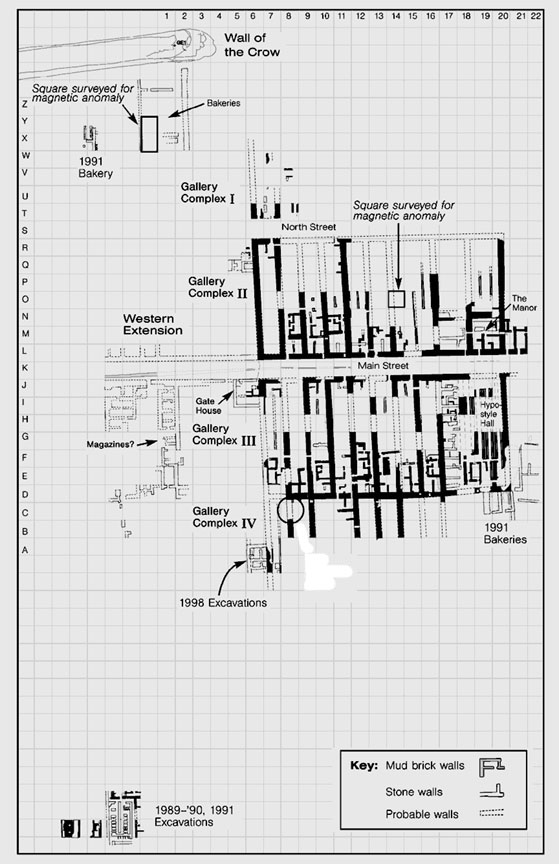

We also mapped a number of grid squares in Zone C itself, demonstrating

another use for magnetic anomaly surveying here. In square O-14 we

found that we could identify where walls, now gone, once stood.

A system of long and substantial gallery walls had been observed running

through Zone C from north to south. One of the gallery walls should

have run through the western corner of this square, but nothing was found.

A careful gradiometer run revealed the reason. The gallery wall had

been there. In ancient times, pottery had piled up against the wall and

its former location was now revealed by the dark pattern running through

the center of O-14 in Figure 5. Sometime

in the ancient past the mud brick gallery wall had been robbed or eroded

away, possibly by floods which had destroyed much of the architecture in

the north and eastern sections of Zone C. The heavier pottery remained,

marking the eastern edge of the gallery wall, which was now a "ghost" wall.

Although the wall was gone, its location is still readily observable with

magnetic anomaly analysis.

Remote Sensing in 2001

I will return to the Giza Plateau in the spring of 2001, armed not only

with our magnetic gradiometer, but with ground penetrating radar.

How I will use these instruments I really can't say. As with magnetometry,

it will take a week or so of experimentation to determine how to get the

most out of the instruments. But as our experiment in magnetometry

has shown, these instruments indeed can provide a valuable data set to compliment

the information obtained through more traditional means.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Figure 2: Gradiometer survey in progress. Becky

Dash operates the FM 36 gradiometer while Glen Dash watches. Both

had to wear surgical scrub suits because the magnetic anomalies were so

weak, on the order of 1/10,000th of the earth’s magnetic field.

These clothes have no metal that could interfere with the survey.

Menkaure's Pyramid rises in the background. At the right the

west end of the Wall of the Crow disappears under the sand.

Figure 3: At Giza, we used traverse lines one-half meter apart

and 10 meters long, taking 40 readings along each traverse.

Figure 3: At Giza, we used traverse lines one-half meter apart

and 10 meters long, taking 40 readings along each traverse.

Figure 4: Results of the gradiometer survey

for the survey area. The darker areas have relatively greater magnetic

field deflection. The north-south alignment and the spacing of the

anomalies indicate the presence of an Old Kingdom structure of some kind.

The right hand corners, where the metal stakes were located, could not be

surveyed because their metal masks any magnetic anomalies. The areas that

were untestable are indicated by the grid-paper like pattern.

Figure 5: Gradiometer results for square O-14.

The dark areas denote buried sherds. The lighter area to the left

is where a gallery wall once stood before it was robbed or eroded away.

The heavier sherds remained where they had piled up against the wall, and

now indicate where the "ghost wall" once stood. The squares that

look like grid-paper are areas that could not be surveyed because of the

presence of metal, primarily metal stakes, which masks magnetic anomalies.